If running is good for you, is running 100 miles better?

ABC News' latest digital documentary, "Ice Runner," focuses on Alicja Barahona, a 64-year-old resident of Greenburgh, Westchester, just outside Manhattan. She's been running ultramarathons for the past 20 years. This year, she tackled the Baikal Ice Marathon, a standard 26.2 miles across a nonstandard terrain: the frozen surface of the deepest lake in the world, Russia’s Lake Baikal in southeast Siberia.

More than 2 million Americans participate in long-distance races -- marathons or more -- each year, and this number is on the rise. Why? Increased public awareness of health benefits of exercise, social media and maybe even the Oprah effect (Oprah Winfrey famously ran the Marine Corps Marathon in 1994).

In general, of course, exercise is your body’s greatest ally. But along with millions tackling 2 miles around the track, a 5K, or even a 26.2-mile marathon, some take running to an extreme with the ultramarathon.

What is an ultramarathon?

There are two types of ultramarathon events: those that cover a specific distance (30 miles, 100 miles) and those that are time-driven; that is, whoever covers the most distance in (24 hours, 48 hours, six days) takes home the laurel wreath. The most common distances are 31, 50, 62 and 100 miles, but there are even races that cover more than 1,000 miles!

What are the effects of running long distances on the heart?

It can be positive for the heart. With intense athletic training, there are some normal changes to the heart, depending on the type of exercise. Triathlon competitors have small increases in size to the heart chambers (ventricles) and small increases in thickness of the heart muscle. These changes are considered adaptive, meaning they are changes that allow the heart an increased ability to pump oxygen and blood to the exercising tissues.

Is there a downside?

Yes, occasionally. As several studies show, those that participate in endurance sports are at increased risk of atrial fibrillation -- an irregular and rapid heart rate -- and atrial flutter -- abnormal heart rhythm -- compared to those that do not participate in endurance sports. Doctors don’t yet know how to prevent this.

“Much of the data points toward atrial fibrillation with long-term running -- it's unclear if it’s related to a single marathon,” explained Dr. Matthew Martinez, associate chief of cardiology at Lehigh Valley Health.

Dr. Micah Eimer, co-director of the sports cardiology program at Northwestern Medicine, advises runners to take it slow.

“Patients who engage in low and moderate intensity exercise can decrease their risk of atrial fibrillation. However, patients who exercise at the extreme levels of exertion appear to have a significantly increased risk of developing atrial fibrillation,” Eimer said.

Runners can feel it and sometimes notice it if they are wearing a heart rate sensor. “Usually they will return the device assuming that it is malfunctioning,” Eimer said. “After they get the same result on a new monitor, they come to the office, where we diagnose them with atrial fibrillation.”

If running is good for us, more running is better, right? Or is 100 miles too much?

Doctors say it’s a matter of running “dosage.”

“Low-level exercise will reduce your risk of dying from heart disease, and up to a point, the more you exercise the lower your risk. But above a certain level -- which is about three times per week -- the benefit is attenuated,” Eimer said, pointing to research on very long-distance runners. “In one study, those patients had a risk level that was the same as patients who did not exercise at all. My recommendation to patients is that moderate exercise strikes the right balance between long-term risk and benefit."

What about runners and sudden death?

Running-related cardiac arrests are rare events, according to several studies. One study of 10.9 million half-marathon/marathon runners from 2000 to 2010 estimated 0.54 deaths per 100,000 participants, which makes marathoning about 20 times less dangerous than riding in a car, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sudden death in people younger than 35, runners or not, is usually due to undiscovered heart defects or overlooked heart abnormalities, which are very rare. The most common cause of sudden cardiac death in the young is a condition called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a rare disorder caused by abnormal genes that lead the heart muscle to grow abnormally thick. Other causes include coronary artery abnormalities (if you are born with coronary arteries that are connected abnormally) and an electrical rhythm problem called Long QT syndrome, an inherited heart disorder that can cause fast, chaotic heartbeats, leading to fainting and potentially death.

Sudden death in people 40 or older is usually due to coronary artery disease.

So, should people be medically evaluated before signing up for a marathon or ultramarathon?

In Italy, young athletes are routinely screened with an electrocardiogram (EKG), which has led to a decrease in sudden cardiac death. However, given the low incidence of sudden cardiac death and the high number of false positive results (detecting an abnormality when there is none), screening all athletes with an EKG is not practical or recommended.

The American Heart Association (AHA) does not recommend the use of diagnostic tests, which are reserved as a follow-up if an initial screening raises suspicions about the presence of heart disease.

But older runners should be careful, doctors say.

Martinez of Lehigh Valley Health said he feels that older patients should “absolutely consult with their local doctor, ideally a sports cardiologist … to discuss overall health, preparation and to understand risks of running a marathon” before lacing up their running shoes.

If you try long-distance running, what should you be aware of?

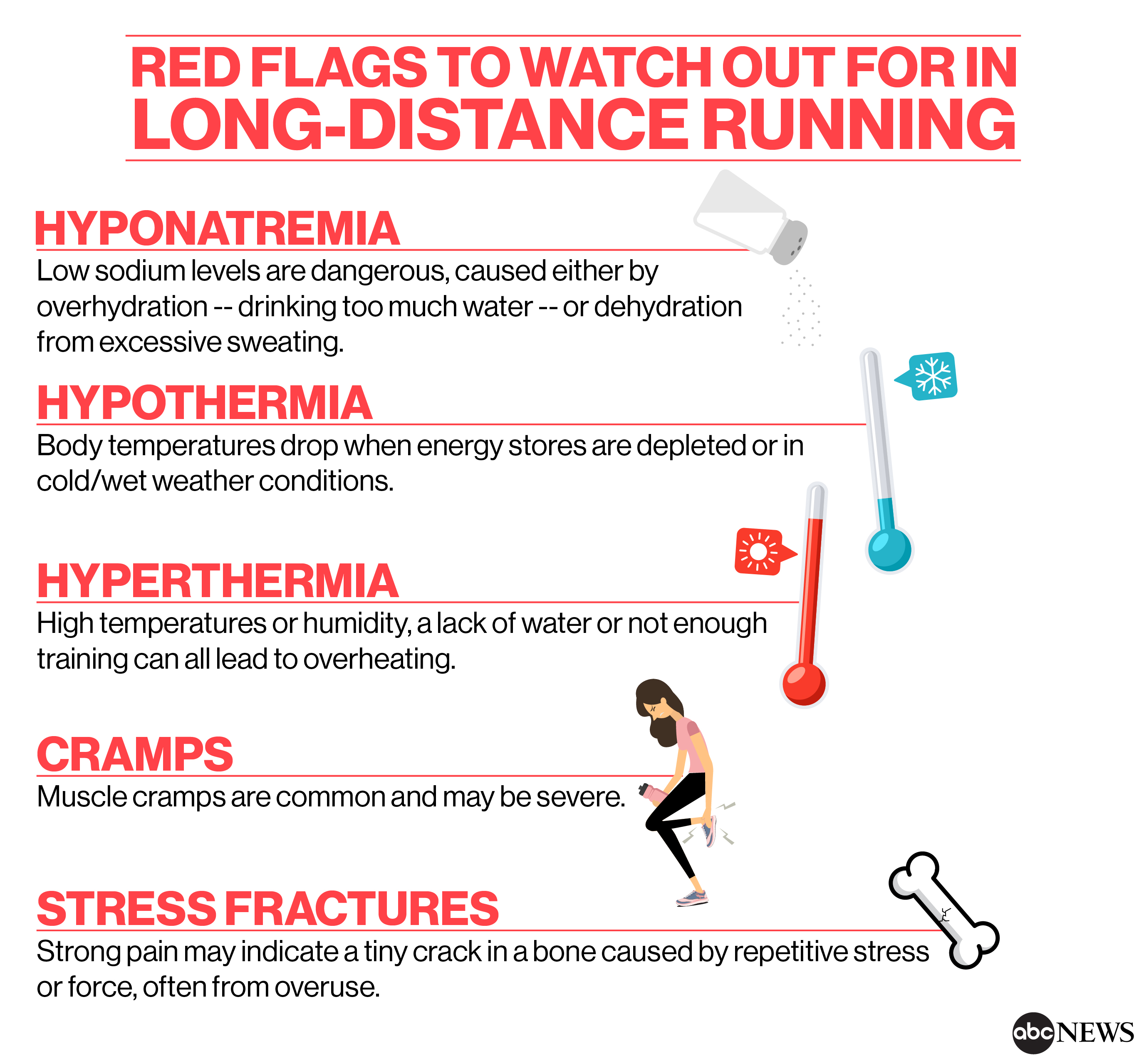

YOUR ELECTROLYTE BALANCE: If you run a lot, you inevitably get thirsty. But drinking too much water can dilute the sodium that should be in your body. In severe cases, this is an emergency. Get help if you have nausea and vomiting, headache, confusion, drowsiness and fatigue. You can also disturb your electrolyte balance if you allow yourself to dehydrate.

HYPOTHERMIA: In cold conditions, runners can slip into hypothermia, in which their body temperatures drop below 95 degrees Fahrenheit internally when energy stores are depleted. Cramps and mental confusion (particularly amnesia) are common. It typically occurs in slow-moving runners, particularly on wet, cold or windy days. To recover, forget the heat sheet -- instead, head inside, get dry and warm, and drink a warm, sugary drink.

HEATSTROKE: Exercise-induced hyperthermia happens when temperatures or humidity are high, the runner hasn’t trained enough, or he or she isn’t drinking enough water. Potentially lethal, heatstroke affects one in 10,000 marathon runners. Symptoms include cramps, shivering and confusion.

For more, see the graphic below:

Is running 100 miles in an ultramarathon good for your knees?

Contrary to popular belief, your knees are probably fine, according to Malachy McHugh, Ph.D., director of research at the Nicholas Institute of Sports Medicine and Athletic Trauma of Northwell Health.

“It is definitely not bad for your knees," McHugh said. "Long-distance runners do not have a higher incidence of osteoarthritis or cartilage damage than non-runners or less extreme runners. In general, running may indirectly may be good for your knees because it will help keep your body mass low, and that will mean less stress on the knees in the long term.”

Advice to heed before picking up long-distance running?

McHugh recommended “talk[ing] to a good sports nutritionist before competing and preferably before starting to train -- it’s an uncommon form of exercise (multiple hours at low intensity) and has some very specific nutritional needs.”

Martinez said to make sure to pay attention to “training, hydration [and] nutrition.”

And if you get blisters? Don’t touch them until your feet are clean and dry, and leave the skin alone. And that’s advice you can use even if you’re just running around the block.

Sunny Intwala, M.D., is a third-year cardiology fellow affiliated with Boston University School of Medicine and a clinical exercise physiologist who works in the ABC News Medical Unit.